The plants are shrivelling like slugs in salt

Actinosphaerums slide here and there

Purple molds grow curly, like colorful hair

My tank is dying and it's all my fault

I wanna help and put a halt

To the frenzy of eating and mating and dying

But I can't stop looking (and I'm not really trying)

My tank is dying and it's all my fault

Under the scope I see a Protist Gestalt

Midges are munching, the moss is still green

But somebody needs to get in there and clean

My tank is dying and it's all my fault

So fill it with hops and add some malt

Boil some wort and mix up the ale

We'll call the result "MicroAquaria Pale"

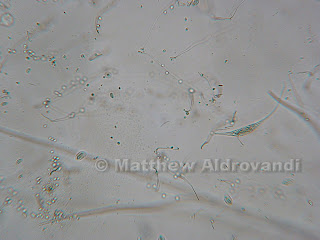

Detail of debris

Look at the death. Observe the wanton destruction. As someone once said about something, "OH, THE HUMANITY!"

This week, I went to the Lab O' Microaquarium on November 6th, from 3:30-4:30. As stated in the above ridiculous attempt at a poem, everything is dying. Or at least, it seems that way...

Detail of debris

You see, the closer one magnifies the view, the more one can see that there is still a lot of life going on, even in spots that look decimated.

Detail of debris

And this just furthers that notion. Note the amount of color in this third picture, as compared to the first. At a distance (magnification), it really looks like nothing is going on, but up close it is a plethora of green. Amazing.

The parrot feather (myriophyllum spicatum) (McFarland, 2012) is dead. Completely dead, and being actively consumed by a variety of organisms.

Detail of filamentous water mold (McFarland, 2012)

Dr. McFarland identified this long, hairy purpley looking stuff as some sort of water mold. You'd think that being mold would subject you to a total lack of movement, and it does, but the stuff moves anyway, probably simply as a mechanism of micro currents in the water. It really looks like a giant snake, though, and I swear it moves of its own accord.

More of the water mold. Note the change in color

in this picture

Amblestegium Sp. (McFarland, 2012)

The moss was still nice and green. The bladderwort and the moss seem to be quite well suited to the sort of cesspool-like environment that I have lovingly set up for them, and although I thought at first that the moss was going to die, it still seems to be quite green.

Unidentified amoeba (McFarland, 2012)

I found this amoeba while cruising around the moss plant. It is really quite striking, both in form and color- this picture doesn't really do it justice; it was a sort of glowing golden color. It wasn't really moving, just sort of pulsing like a weird, blobby UFO. I believe the upper right hand dot in it might be the nucleus.

Utricularia Gibba (McFarland, 2012) feeding structure

The bladderwort (Utricularia Gibba) seems to be doing just fine. I love its symmetry. You can appreciate the perfection in the cells from this distance, but closer it is even more beautiful.

Bladderwort detail

I love how green it is, but I especially love the way that the cells fit together like a web, or a honeycomb. How does nature do it?

Eating the bladderwort, or perhaps just some debris on its surface, was a euchlanis rotifer, identified by the unflappable Dr. McFarland. I thought it looked just like a miniature potato bug, and in fact, I had mistook one of these during the first viewing of the MicroAquarium for a copepod. The way that it moves is really interesting; it hooks its tail on to the plant and then eats everything within reach.

Series of pictures of Euchlanis Rotifer

In the above "action shots", you can see clearly the type of movement I was talking about. These guys move fast, so I just kept snapping til I had a few good ones.

Series of pictures of flagellate organisms

These two pictures are of flagellates (McFarland, 2012). They have flagella, which is hard to see in these shots, but clear on the microscope. Dr. McFarland thought that these two might have just finished reproducing by binary fission (I, with the mind of a 6th grader, thought they were mating).

Series of pictures of Litonotus (McFarland, 2012)

The above photos show an interesting organism, Litonotus. It is identified by its parallel rows of cilia, which it uses in part to feed, and in part to move (Patterson, et al, 1998). It is part of a group of predatory and scavenging ciliates, and it uses toxicysts, also called extrusomes, to capture and devour food. It moves much like a common earthworm, elongating its body and then shortening it.

Series of pictures of Arcella leaving its test

(McFarland, 2012)

The four photos above are nothing short of amazing. As we looked on, this Arcella left its test completely. In the first shot, you can see it in there, sort of swirling about, and then it changes subtly, a ring forming around the outside. All of a sudden, the thing just squeezed out and left its test behind like a bad habit.

Arcella are initially colorless, but their test changes quickly to a brownish color due to the absorbtion of metal salts in the water (Patterson, et al, 1998). The nucleus in these creatures is prominent, and it has a hole called a ventral aperture that exudes the appendage that controls movement, as well as the feeding pseudopodia. The test is a layer on the outside of the organism that is soft and meshlike. This organism feeds on small particles in the water.

Wow. A lot happened this week, and there is only one more week til the end of the world (for MicroAquariums, at least). Til next time.

Bibliography:

1. Patterson, DJ. Hedley, S. 1998. Freeliving Freshwater Protozoa: A Colour Guide. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

2. McFarland, Ken. [Internet] Botany 112 Fall 2012; 2012. [cited November 2012] Available from: http://www.botany1112012.blogspot.com

.JPG)

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment